The Sceptre of Hermes – Part One

Harold Wright was a dentist by profession, practising in the American city of Philadelphia. His lifelong interest and hobby, however, was the study of anthropology.

It was this pursuit which frequently took him to distant lands to study the culture and behaviour of aboriginal societies, and it was his curiosity about traditional jungle medicine which took him one day to a remote area of Peru.

Canoeing on the Maranon river in Peru

On this occasion Wright was travelling in a canoe down one of the tributaries of the Marañón river. He was accompanied by a Jivaro Indian named Gabrio, who had agreed to guide him through the territory of the Huambiza tribe in search of a brujo or medicine man.

Their journey had thus far proved unsuccessful, as the Indian communities with whom they had come in contact were suspicious of wealthy white intruders. Wright began to think that his quest had been in vain.

Then one morning, shortly before he was due to return to Philadelphia, Gabrio complained to him that his jaw was swollen, and that he was in considerable pain. From what Wright could make out he seemed to be suffering from an infected tooth.

Wright explained to his guide that he was a trained “tooth” doctor who was well qualified to deal with his problem. But Gabrio adamantly refused his aid, claiming that the white man’s medicine was not good for the Indian.

A short while later, as they were paddling along the river, a small jungle village hove into sight. Gabrio immediately beached the canoe and went off in search of the resident medicine man.

When he returned a few minutes later, he was accompanied by a thin, emaciated old man who was clearly the local brujo. Gabrio explained the nature of his problem to him, whereupon the elderly man squatted down and placed Gabrio’s head firmly between his knees.

After probing with his fingers around the inflamed gums for a while, the brujo uttered a grunt of satisfaction. He then called to his assistant, who brought a bowl filled with a dark, oily liquid, which the medicine man proceeded to swallow with a single gulp.

Wright was hardly surprised when the man suddenly vomited the contents on the ground in front of him. Undeterred by this event, the man called for a second bowl and the identical scene repeated itself.

With the aid of his assistant, the medicine man then pulled Gabrio to the ground and crouched over him. He then placed the contents of a tobacco-like pouch into his mouth and began chewing furiously, all the while chanting in a thin, reedy monotone.

As Wright looked on with interest, the witchdoctor leaned forward, placed his mouth against Gabrio’s swollen cheek, and began to suck noisily. The pressure on the tender gums caused the Indian to let out a yelp of pain.

The old man continued to suck vigorously until he suddenly raised his head and spat something out onto the ground. Wright drew closer and saw that it was a splinter of wood. The witchdoctor continued to suck, and soon spat out another mouthful. This time it was a collection of ants.

Wright was amazed to see that a third expectoration produced a grasshopper, and that the fourth delivered a dead lizard. The brujo then picked up this last creature and dangled it by its tail in front of the enthusiastic crowd of Indians that had gathered around to watch.

Gabrio gazed at these objects in astonishment, but it was clear that he was still in considerable pain. The old man then picked up an open mussel shell and, using it as a pair of tongs, proceeded to pluck a live coal from a nearby fire. He then crushed some dry leaves into a fine powder and sprinkled this upon the glowing coal.

Then, turning to Gabrio, he motioned him to place the shell in his mouth. As he did so, the fumes from the burning powder curled slowly out of Gabrio’s mouth. After a few minutes of this treatment Gabrio removed the shell with its smoking contents, and announced to the group that his jaw was healed and that the pain had disappeared.

He told Wright that he was ready to continue their journey down river. Before they left, Wright was able to obtain some of the leaves which had been used in the cure. When he returned to the United States he had them analysed, to see if they contained some healing or anaesthetic property.

Subsequent laboratory analysis revealed that the leaves were taken from a variety of the babassu plant. Yet to his surprise, Wright learned that they contained nothing which could possibly have accounted for the abrupt cure of Gabrio’s swollen jaw.

The Indian had effectively been healed, but by a substance which apparently held no curative powers. As Wright later confided to a friend about this strange incident: “What I cannot understand is how a toothache can be cured without medicine or surgery.”

Yet the brujo had healed Gabrio’s pain in the space of half an hour, in a way which Wright with all his dental skill could not have matched. 1

In 1966, another American doctor had an unusual experience in South America. His name was Andrija Puharich. Puharich was a physician who had distinguished himself in the field of medical technology, having invented a variety of miniature devices to assist the hard of hearing.

In 1966, another American doctor had an unusual experience in South America. His name was Andrija Puharich. Puharich was a physician who had distinguished himself in the field of medical technology, having invented a variety of miniature devices to assist the hard of hearing.

He was also a researcher of psychic phenomena, having conducted investigations of such gifted clairvoyants as Eileen Garrett, Harry Stone and Peter Hurkos. It was his interest in the unusual which led Puharich to Brazil, to see firsthand the exploits of a certain psychic surgeon named José Arigo.

He travelled to Congonhas de Campo in the state of Minas Gerais to observe this unusual healer in action. It so happened that, prior to his visit to Brazil, Puharich had been suffering from a growth of tissue on his arm. Since his own physician had found this growth to be non-malignant, he had recommended that it be left untreated.

Puharich was aware that the growth was extremely near the nerve controlling the movement of his little finger. He was afraid that any further growth in size could lead to muscle contraction which might paralyse his finger.

In due course, therefore, after having witnessed Arigo performing various surgical procedures which appeared to be successful, Puharich asked him if something could be done about the growth on his arm.

Arigo examined it closely, and then turned to those who were still waiting for attention, and asked if any of them possessed a knife. Of the several that were offered, Arigo selected one, and passed it on to Puharich for inspection. The American found it to be a common pocketknife, which he then returned to the healer.

Then, without attempting to sterilise the knife in any way, Arigo grasped Puharich’s arm and made a swift incision. Blood immediately began to ooze from the cut. Arigo then pressed his fingers on either side of the incision and began to apply pressure to the opening.

As Puharich watched, a small tumour emerged and dropped onto the floor. Although the cut was only about one centimetre in length, Puharich was surprised to see that the tumour which lay on the floor was about three centimeters in diameter.

Although the incision in Puharich’s arm was not sutured or treated in any way, it healed completely within forty-eight hours. Puharich noted later that while a western-trained surgeon would have required at least fifteen minutes to perform this excision, the entire operation conducted by Arigo had lasted less than fifteen seconds. 2

1966 was also the year in which Lynn Brailler, the wife of an American physician, was involved in a motor vehicle accident. In this collision she suffered serious injuries to her neck and spine, which required her to wear a neck brace to support her damaged limbs.

These injuries caused her intense pain, and she resorted to various drugs to gain relief. When large amounts of aspirin were no longer effective, she switched to codeine. The presence of the neck brace did little to ease the pain, which continued unabated for the next three years.

It was then that Lynn was told that she had acquired a terminal disease of her spinal cord. Despite this alarming diagnosis, she was convinced that her pain was due to a cervical disc injury.

It was another three years before her specialist concluded that she did, in fact, have a disc problem which required surgery. By this time the majority of the muscles in Lynn’s neck, back and right arm had atrophied from lack of use.

An operation was then performed in which pieces from her hipbone were transferred to her neck. The surgeon estimated that this disc fusion operation would take another two years to heal completely, and he warned Lynn to be particularly careful during this time, as any sudden blow could cause her to break her neck.

In May 1975, almost nine years after the original accident, Lynn was out shopping when the car in which she was travelling was struck broadside by a truck that had careened through a red traffic light. In this collision, Lynn again suffered injuries to her neck. The two discs which had previously been fused together had shattered.

Although her neck required another operation which would again involve a transplant from her hip, the surgeon chose not to operate because her spine was in such a fragile condition, and because he was fearful that another operation might sever her spinal cord completely and leave her paralysed.

Instead, he directed her to rest in bed and to treat her injured neck with applications of hot packs. For Lynn the pain which had been bad before, now became intolerable, and she dosed herself with increasing amounts of codeine and valium.

Lynn Brailler was faced with the choice of a protracted and extremely painful convalescence in bed, which would entail resigning from her job, or else of undergoing dangerous surgery which could leave her a quadriplegic.

She had already decided on the latter course of action when she chanced to pick up a journal which contained an article by the noted psychic healer Olga Worrall. Although Lynn had never been able to bring herself to believe in such a thing as faith healing, a friend of hers persuaded her to telephone the healer in Baltimore.

Lynn spoke to Worrall, who expressed interest in her case and invited her to attend one of her healing clinics. Before making a decision, however, Lynn discussed the matter with her husband.

“It’s not going to help you to go over there,” he declared emphatically. “Somehow in your mind you’ll think you’ve tried everything, that nothing will work, and you’re going to be more depressed than ever.” 3

Despite her own misgivings, and against the advice of her husband, Lynn decided to undertake the trip from Washington to Baltimore.

When she arrived at the church where the healing sessions were to take place, Lynn suddenly felt overcome by embarrassment at having succumbed to such an improbable course of action. As she sat in the pew with her arm in a sling and her neck in a brace, it seemed obvious that nothing could be done for her.

Later, when various people began to make their way to the altar rail, she felt that she simply could not bring herself to join them. It was her friend who insisted that she do so, and practically pushed her down the aisle. Lynn described what happened then.

“I never felt so foolish in my whole life. For me to kneel down at a rail was just too much. Olga came along and put a hand on either side of my head, and I thought, Humpf!, big psychic! She doesn’t even know where the problem is.

But then, I knew she wasn’t for real anyway. I was thinking what a waste of time, when suddenly I felt a deep heat going through the inside of me, through my back and into my arms. When she took her hands away from my head, the heat dissipated.” 4

As she retraced her steps from the altar rail, Lynn was convinced that she was, if anything, even more seriously hurt than before. She felt that the action of the healer had actually added to her injuries. She sat out the remainder of the service in a state of shock.

As she was leaving the church, however, Lynn noticed that both her arms felt perfectly normal. She found that she was able to raise her right arm, still in its sling, without the usual searing “tear response” which inevitably attended any movement.

Furthermore, the agonising pain in her neck had been reduced to a mere ache. Thinking that this was a temporary effect caused by her state of shock, Lynn waited for the pain to return. But by the time she reached her home in Washington, D.C., the pain had still not returned.

Her husband greeted her skeptically, saying: “Well, did you get healed?” In response, Lynn flailed both her arms and moved her neck and cried, “Did I ever get healed!” Her husband looked at her in stunned amazement.

“The poor man! I felt sorry. I just watched the color drain from his face, and he was listing a little to the left. Finally he said, ‘Do that again’, and I did. You know how you always have to repeat everything for scientific validity.” 5

For Lynn Brailler, almost ten years of suffering and intense pain had come to a sudden and dramatic end. Her neck injuries had been completely healed.

The experiences which occurred to Harry Wright, Andrija Puharich and Lynn Brailler, are instances of physical healing which defy explanation in conventional western medical terms.

Because they do not fall within the accepted mould of western medical thinking, cases such as these are generally regarded as spurious, as contraventions of reality. Where they are not condemned as outright fraud, they are rejected as the result of suggestion and imagination.

They are not considered to be cases of valid medical procedures. But while the cures that were witnessed by these three people may seem inexplicable within our own definition of reality, they nevertheless find a legitimate place within the mental framework of other cultural patterns of belief.

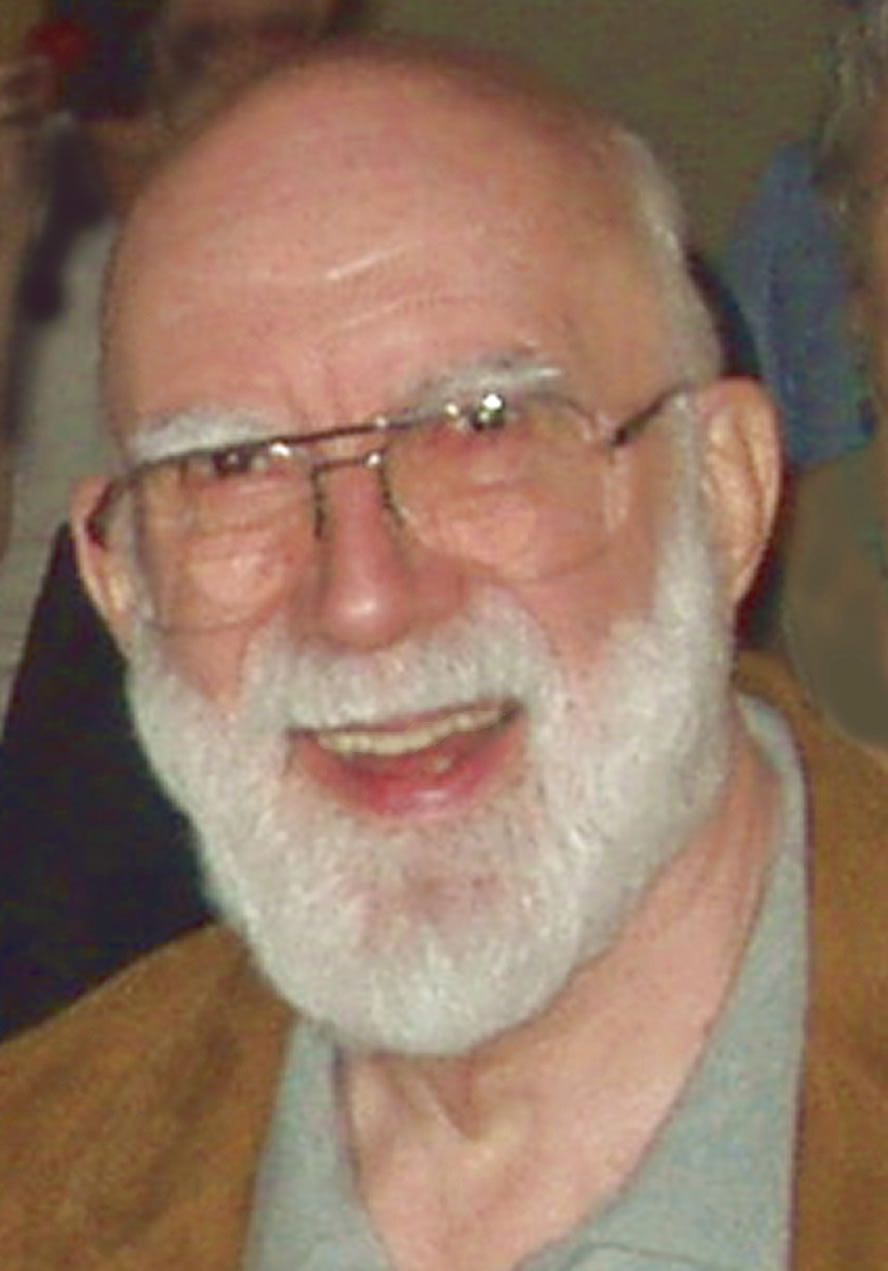

Michael Harner

Michael Harner was a teacher of anthropology at the Graduate Faculty of the New School for Social Research in New York. He was not, however, the usual type of teacher one might expect to find within this academic discipline.

Harner was a recognised shaman, having received his shamanistic training from the Jivaro Indians on the eastern slopes of the South American Andes, as well as with the Conibo Indians of the Ucayali River region of the Peruvian Amazon.

For Harner, shamanism was not mere mumbo-jumbo, or some pseudo-medical subterfuge played upon the gullibility of simple minds. Rather, it was an exquisitely refined social and psychological paradigm, based upon an alternate view of reality. As he described it:

“Shamanism is a great mental and emotional adventure, one in which the patient as well as the shaman-healer are involved. Through his heroic journey and efforts, the shaman helps his patients transcend their normal, ordinary definition of reality, including the definition of themselves as ill.

“The shaman shows his patients that they are not emotionally and spiritually alone in their struggles against illness and death. The shaman shares his special powers and convinces his patients on a deep level of consciousness, that another human is willing to offer up his own self to help them.

“The shaman’s self-sacrifice calls forth commensurate emotional commitment from his patients, a sense of obligation to struggle alongside the shaman to save one’s self. Caring and curing go hand in hand.” 6

For Harner, shamanism is not a practice which can be separated from the mental paradigm in which it has its roots. Its validity lies in its value in sustaining the social fabric of the tribe, and its ability to diagnose and treat disease within the context of that psychological setting.

The mental paradigm under which the shaman operates, is not the paradigm held by the modern medical practitioner. The witchdoctor and the brujo function within a description of the universe which is profoundly different from the western way of thinking.

Its efficacy is not denied by the validity of the western scientific paradigm. Both descriptions of the universe are valid within their own contexts of belief. It is the belief in each underlying system which generates results. These beliefs are not confined to any special society. They can in fact be transferred from one group to another. They can be learned as the need arises.

For example, by using those same methods by which he was taught, Harner has conducted training workshops in shamanistic healing throughout Europe and North America.

He has found that westerners can successfully practice shamanism, if they are prepared to set aside their usual systems of belief and conventional assumptions of reality.

As he stresses to his students, it is not necessary to understand how shamanism works in order to practise shamanistic healing, just as it is not necessary to understand the principle of electricity to operate a motor vehicle or radio. All that is necessary is to permit one’s self the freedom of believing in its possibility.

With that as a base, the subsequent results speak for themselves, and are their own proof of the validity of the shamanistic way of healing. Harner has demonstrated that shamanism does not draw its worth from the gullibility of primitive minds. It is potentially as effective within western technological society as it is within the aboriginal world.

What determines its effectiveness is the underlying foundation of belief.

When Harold Wright witnessed the strange ritual on the banks of the Marañón river in Peru, his western scientific training led him to believe that the efforts of the Jivaro brujo were mere sleight-of-hand tricks designed to prey upon the gullibility of his guide Gabrio.

It was clear to Wright that the various objects which the medicine man spat onto the sand were objects which he had previously extracted from his tobacco-like pouch, slipped surreptitiously into his mouth, and then regurgitated at the appropriate psychological moment.

To Wright, there seemed nothing of real medical value in the entire performance, other than the inescapable fact that it cured Gabrio of his painful condition.

Yet Harner has pointed out that the various creatures which the medicine man produced were not simply a collection of extraneous objects gathered at random. Each object was actually a tsentsak, or magical dart, which was essential to the shamanistic method of healing.

According to the shamanistic paradigm of belief, the tsentsak, or spirit helpers, are powers which are believed to cause and cure disease. Non-shamans are naturally unable to see these spirit helpers because they do not share the shamanistic state of consciousness. To the shaman, however, they are vividly real.

Harner explains the significance of these spirit helpers, and the role they play in the restoration of health.

“Each tsentsak has an ordinary and nonordinary aspect. The magical dart’s ordinary aspect is an ordinary material object, as seen without drinking ayahuasca. But the non-ordinary and “true” aspect of the tsentsak is revealed to the shaman by taking the drink.

“When he does this, the magical darts appear in their hidden forms as spirit helpers, such as giant butterflies, jaguars, serpents, birds and monkeys, who actively assist the shaman in his tasks.

“When a healing shaman is called in to treat a patient, his first task is diagnostic. He drinks ayahuasca, green tobacco water, and sometimes the juice of a plant called piripiri. The consciousness changing substances permit him to see into the body of the patient as though it were glass.

“If the illness is due to sorcery, the healing shaman will see the intruding non-ordinary entity within the patient’s body clearly enough to determine whether he possesses the appropriate spirit helper to extract it by sucking.

“When he is ready to suck, the shaman keeps two tsentsak, of the type identical to the one he has seen in the patient’s body, in the front and rear of his mouth. They are present in both their material and nonmaterial aspects, and are there to catch the non-ordinary aspect of the magical dart when the shaman sucks it out of the patient’s body.

“He then “vomits” out this object and displays it to the patient and his family saying, “Now I have sucked it out. Here it is.” The non-shamans may think that the material object itself is what has been sucked out, and the shaman does not disillusion them.

“To explain to the layman that he already had these objects in his mouth would serve no fruitful purpose and would prevent him from displaying such an object as proof that he had effected the cure.” 7

Psychic surgeon Tony Agpaoa

Among the psychic surgeons of the Philippines and Brazil, the ability to operate within a unique framework of reality, other than the normal state of mind, is crucial to the healer’s craft. Like the shaman, the psychic surgeon works within a specific framework of belief, which is linked in turn to those cultural values which lend it its validity.

Western observers, who have watched psychic surgeons at work, have made much play of the fact that these “surgeons” seldom actually penetrate the skin of their patients, but manipulate instead their outer flesh.

They point out that laboratory analyses of the tumours and other tissues which emerge from such surgery often reveal no organic link with the patient concerned. Surgeons even produce bizarre objects such as feathers and pips, which could never have been part of the bodies of their patients.

Furthermore, the blood, which usually appears in such profusion at these surgical operations, is often found to belong to pigs or chickens, or to some other non-human source. To critically trained observers of the west, these absurdities are taken to be clear evidence of medical fraud – a charade played upon the ignorance of their patients.

Yet this judgement is merely a reflection of the way in which these effects are construed within the western paradigm of thought. But the phenomena of one paradigm can never be validated within the context of another.

The physical objects which the shaman spits out, or the tissues which the psychic surgeon excises, cannot be interpreted correctly within the context of the western framework of belief. These things are visitors from another paradigm.

They can have no value within the western medical mould of thinking, just as the idea of pathological bacteria has no significance within the shamanistic scheme.

The objects conjured up by psychic healers are actually materialisations, or apports created by the healer, which serve as physical evidence induced to enforce belief that effective treatment has actually taken place.

As Dr. Hiroshi Motoyama was told when he challenged the Philippine psychic surgeon Tony Agpaoa:

“I asked Tony Agpaoa why he finds it necessary to produce immediate, physically apprehensible results (such as blood) during the operation. Tony said that it is actually unnecessary to produce blood or tissue to cure a person, but he held that people will become more convinced of the existence of higher dimensions of being if they witness the materializations of physical objects through non-physical means, and that such immediate experience is necessary to shock materialistically oriented people into spiritual growth.” 8

(Continued in Part Two)

References

1 Harry Wright, “Witness to Witchcraft“, Funk and Wagnalls, New York, 1957, pp. 8-15.

2 Gene Klinger, “Jose Arigo or Dr Fritz?” Fate magazine, December, 1967, pp. 95-96.

3 James Crenshaw, “A New View of Healing“, Fate magazine, May 1979, pp. 89-90.

4 Ibid, p. 90.

5 Ibid, p. 91.

6 Michael Harner, “The Way of the Shaman“, Bantam, New York, 1982, pp. xiii-xiv.

7 Ibid, pp. 21-23.

8 Hireshi Motoyama with Rande Brown, “Science and the Evolution of Consciousness“, Autumn Press, Brookline, 1978, p. 127.