The Legend of Lemuria – Part Two

When the sixteenth century English poet John Donne penned the famous words “No man is an island”, he used the image of a tiny island, lost in a vast ocean and cut off from everything else in the world, to convey the idea of complete and total isolation.

The Lost Island of Rapa Nui (Easter Island)

There is perhaps no better example of what Donne had in mind than the Polynesian island of Rapa Nui, or to give it its modern name, Easter Island. Unlike so many islands located in other parts of the Pacific Ocean, Easter Island is not an archipelago or chain of islands.

Instead, it is a tiny outcrop of volcanic rock with nothing but open ocean around it for thousands of miles in every direction. In fact the nearest inhabited land is Pitcairn Island some 1,300 miles (2,800 kms) away, while its nearest continental neighbour is central Chile, almost 2,200 miles (3,500 kms) to the East.

Easter Island is minute. It is shaped in the form of a triangle, with an extinct volcano located at each of the three corners. It is roughly 15 miles (24 kms) long and 7.6 miles (12.3 kms) wide. It has no permanent streams or rivers, so locals must rely on rain-filled lakes for drinking water.

Given its extreme isolation, its lack of resources and the distance from surrounding land, it is remarkable that it was ever able to sustain human life. Yet when the Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen first discovered it on Easter Sunday in1722, it was found to have a population estimated at between two and three thousand people of Polynesian origin.

The Stone Statues

The Stone Statues (Moai) of Easter Island

But what has made Easter Island such a conundrum to so many, and why it has become such a magnet for mystery seekers ever since, is that it was found to be the home of about 900 stone statues called Moai, that were carved in stylized human form.

Most of these statues were carved from compressed volcanic ash, called Tuff. However, 13 Moai were found to be carved from Basalt, 22 from Trachyte (a type of igneous volcanic rock), and 17 from fragile Red Scoria, found in various locations on the island.

The average height of these stone Moai was about 13 feet (4 metres), with a base of around 5 feet (1.5 metres), and the average weight of these stone statues was around 14 tons. However, a few of these massive creations towered over all the others.

The tallest Moai ever erected was called Paro. It was found to be almost 33 feet (10 metres) high, and weighed 82 tons. But even this was later dwarfed by another Moai known as “El Gigante”. This unfinished sculpture, still embedded in rock near the Rano Raraku quarry, would have been 69 feet (21 metres) tall when completed, with a weight of over 160 tons.

Early western visitors found it hard to comprehend how an island so small, with a population of a mere few thousand souls, could have constructed stone monuments on so massive a scale, especially when nothing like it was to be found anywhere else in the history of Polynesian culture.

One of the first westerners to draw attention to the mystery of the Moai was the Norwegian adventurer Thor Heyerdahl. In 1947, Heyerdahl and his crew were successful in sailing a hand-built balsa wood raft named the Kon-Tiki, from South America to the Tuamotu Islands in French Polynesia.

This 5,000 mile (8,000 kms) journey later brought Heyerdahl world-wide fame, when the story of his epic journey across the open ocean was published under the title The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas.

In 1955, Heyerdahl organized a team of professional archeologists drawn from different countries to travel to Easter Island, where they spent many months exploring various archeological sites. They also conducted experiments in the carving, transportation and erection of various stone Moai.

Moai Smashed Into Pieces

Heyerdahl’s team made two important discoveries. The first was that these stone statues fell into two groups. The first group comprised those Moai that were undamaged and still standing. The second group consisted of Moai that had been smashed into pieces.

The significant part of this discovery was that the undamaged Moai were found to be clustered around the inner and outer slopes of a volcanic crater known as Rano Raraku, where the majority of these statues had been carved, while the smashed statues were found at various points along the coastline of the island.

The second discovery of Heyerdahl’s team was that the heads of the statues that lay scattered around Rano Raraku crater were actually partially buried. And just like icebergs, whose major bulk lies hidden below the water, these stone statues were found to have torsos many times larger than their protruding heads.

Excavated Moai

Several of these partially buried Moai have subsequently been excavated, exposing the full extent of the bodies that previously lay hidden beneath the soil. They reveal heavy torsos with narrow arms carved in bas relief, and long slender fingers and thumbs that sometimes point to the navel.

In contrast with the undamaged statues located on the slopes of Rano Raraku crater, hardly any of those found along the sea shore were found to be intact. Often their heads were snapped from their bodies, and in some cases lay almost unrecognizable, being little more than a pile of stones.

It has only been through the enduring efforts of archeologists like the American William Mulloy and his protégé Sergio Rapu Haoa, Chilean Claudio Cristino, as well as the generous funding offered by various commercial corporations, that about 50 Moai have since been re-erected on their Ahus (stone platforms).

However, at the time of his visit in 1955, there was one particular feature which made a powerful impression on Heyerdahl and his team. That was state in which they found the quarry site at Rano Raraku crater.

As Heyerdahl later recorded in his book, from the chaos and disorder that was evident at the site, it appeared as if a sudden disaster had overtaken the island, causing the sculptors to cease what they were doing and flee from the site, leaving their stone tools and unfinished Moai behind them.

The Megalithic Wall

The Megalithic Wall at Ahu Vinapu

Yet another mystery that confronted Heyerdahl and his team, was the cyclopean stone wall that he discovered at a place called Ahu Vinapu, just to the east of what is now the main town of Hanga Roa, and situated not far from the end of the main airport runway.

Heyerdahl found that this partially destroyed wall was built out of enormous, polished, blocks of basalt that weighed up to seven tons each. Yet the stones of this wall fitted together so perfectly that they seemed capable of withstanding the power of even the strongest earthquake.

The megalithic wall located at Ahu Vinapu is unique. Not only is there no other site on Easter Island that can compare with it, but nothing that has been found on any of the other islands throughout the entire Pacific Ocean can match it for its precision, size and design.

The only type of construction that rivals it elsewhere on the planet are the pyramids of Egypt, and the cyclopean structures found in various parts of South America. This led Heyerdahl to speculate that the wall might be evidence of contact with South American cultures in the ancient past.

Petroglyphs

Bird-man Petroglyph at Orongo

Another feature of Easter Island that has led to widespread conjecture over the years is the enormous number of petroglyphs, or pictures, that have been carved into the rocks on nearly every available surface. In fact over 4,000 glyphs have now been catalogued at more than a thousand different sites.

Easter Island has by far the richest assortment of petroglyphs in all of Polynesia. They can be found displayed upon the rocks, inside caves, on the walls of houses, and in some cases have even been found carved upon the Moai themselves. They come in a wide variety of designs.

These designs are sometimes representations of marine animals such as turtles, tuna, swordfish, sharks, whales and dolphins. In other cases they include such things as frigate birds, roosters and canoes. Although not as well known as the famous Moai, these petroglyphs were considered sacred images.

But those that have aroused the greatest interest are the famous “Bird-man” glyphs that can be found near the crater at Orongo. This emblem of Tangata Manu the Bird-man, consisted of a crouching human with the head of a bird, and was the symbol of a cult involving various clans on the island.

The most popular of these cult festivities was the annual Bird-man ritual, which was held on a narrow ridge with a deep crater on one side, and a thousand foot drop into the ocean on the other. The aim of this ritual was to be the first person to return with the egg of a Sooty Tern taken from the offshore islet below.

But what has made the Bird-man glyphs so significant, is that they were not only carved on the rocks around Easter Island, but that they also featured in one of the most enigmatic phenomena that have been found on Easter Island, and that is the mysterious form of writing known as Rongorongo.

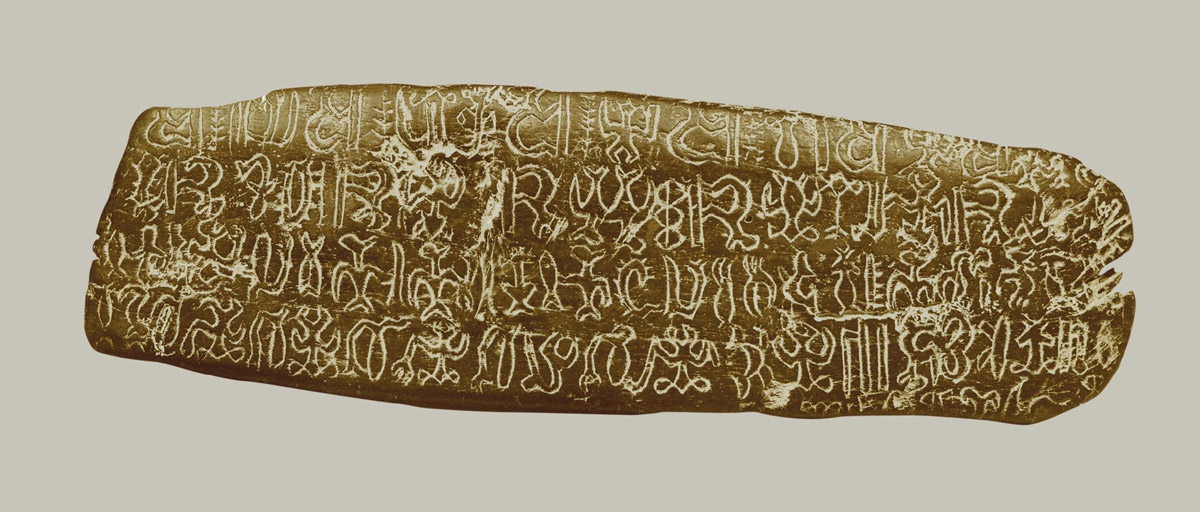

Rongorongo

This strange written script was first discovered in 1864 by the French missionary Eugene Eyraud. As he noted in his journal at the time:

“In every hut one finds wooden tablets or sticks covered in several sorts of hieroglyphic characters: They are depictions of animals unknown on the island, which the natives draw with sharp stones.

“Each figure has its own name; but the scant attention they pay to these tablets leads me to think that these characters, remnants of some more primitive writing, are now for them a habitual practice which they keep without seeking its meaning.” (Eyraud 1866:71)

The script that Brother Eyraud found on those wooden tablets was referred to by the local natives as Rongorongo. According to the Rapanui language which they spoke, Rongorongo meant “to recite or chant out”, meaning that it was supposed to be recited or chanted out loud.

Four years after Eyraud first saw these wooden tablets on Easter Island, the Bishop of Tahiti received a gift of human hair wrapped around a small wooden board. When he found that the board was also covered in hieroglyphic writing, he recognized that this could be a discovery of profound importance.

He therefore wrote to Father Roussel on Easter island, asking him collect all the tablets that he could find, and to see whether any islanders remained who could interpret them. But Roussel reported that he could only recover a few, and that none of the natives left on the island knew how to read them.

To this day only about two dozen wooden objects bearing Rongorongo inscriptions remain. These heavily weathered and partially damaged records were collected in the late 19th century, and can now only be seen in museums and private collections.

None of these examples of Rongorongo writing can be found on Easter island today, although the possibility does exist that some may have been secreted away in lava tubes, or in family caves that adorn the sides of the Orongo crater.

What has made this script so perplexing was the fact that it was later found to have been written in a style of writing called reverse Boustrophedon, where successive lines are written alternately from right to left, turned upside down, and then from left to right.

A remarkable fact about this reverse Boustrophedon style of writing, was that it was also similar to that used by the ancient Greeks, the Etruscans and the Hittites, as well as in the Indus valley, by the long vanished cultures of Mohenjo Daro and Harappa.

Similarities Between Indus Valley and Easter Island (Rongorongo) Glyphs

What makes this association even more compelling is that many of the glyphs taken from Indus valley scripts are almost identical to those used in Rongorongo, as can be seen from the accompanying ilustration. (See photo)

The writing itself consisted of a series of glyphs, or stylized pictorial characters. These glyphs contained about 120 basic elements, composed of Bird-men in a variety of positions, as well as birds, animals, plants, celestial objects and geometrical shapes.

However, these basic elements could also be combined together to form up to 16,000 other glyphs. It soon became clear to linguistic scholars that Rongorongo was a highly complex and sophisticated form of writing. Yet even to this day it has never been deciphered.

Sadly, those few clan elders who were said to be still able to understand the Rongorongo script at the time of Reynaud soon succumbed, some as a result of the Peruvian slave raid of 1862, and others from the subsequent epidemics of smallpox and tuberculosis which the slave traders brought to the island.

Questions and Answers

The many mysteries that can be found on Easter Island raise the following critical questions:

– Who exactly built the stone statues on Easter Island?

– How did they carve them out of the solid rock?

– How did they transport them?

– When did they build them?

– Why did they build them?

– Did the same people who built the statues also carve the petroglyphs?

– Did these same people also build the megalithic wall at Ahu Vinapu?

– Were these same people responsible for creating the Rongorongo script?

Prior to his arrival on Easter Island, it is doubtful if Thor Heyerdahl was aware of James Churchward, or of his claim that there once had existed a vast continent in the Pacific Ocean that had been devastated by a series of cataclysms, and had sunk beneath the waves, as explained in Part One.

Cyclopean Stone Ruins at Sacsayhuaman in Peru

But even if he had been, it is likely that he would simply have dismissed Churchward’s theory as fictional legend. Because of the similarities in stonework found on the island with that of the Incas, Heyerdahl favoured the idea that the original stone builders had come to Easter Island from Peru.

However, modern archeologists have concluded that, because Polynesians were found living on Easter Island when Westerners explorers first arrived, that it must have been the Polynesians themselves who were responsible for all of these enigmatic features, from the statues to the petroglyphs and the writing,

According to this conventional theory, Easter Island was most likely first populated by Polynesian settlers, who arrived in their canoes and catamarans from other island chains in the Eastern Pacific, such as the Gambier Islands or the Marquesas Islands.

It was noted that when the British explorer James Cook called in at Easter Island in 1774, one of his crew members who came from Bora Bora in French Polynesia, was able to communicate with the islanders in his native language.

A report issued recently by National Geographic had this to say about the origins of Easter Island:

“It’s not clear when the islands were first settled; estimates range from A.D. 800 to 1200. It’s also not clear how quickly the island ecosystem was wrecked—but a major factor appears to be the cutting of millions of giant palms to clear fields or make fires.

“It is possible that Polynesian rats, arriving with human settlers, may have eaten enough seeds to help to decimate the trees. Either way, loss of the trees exposed the island’s rich volcanic soils to serious erosion. When Europeans arrived in 1722, they found the island mostly barren and its inhabitants few.”

The report went on to add this comment regarding the mysterious Moai:

“Rapa Nui’s mysterious moai statues stand in silence but speak volumes about the achievements of their creators… The effort to construct these monuments and move them around the island must have been considerable -but no one knows exactly why the Rapa Nui people undertook such a task.

“Most scholars suspect that the moai were created to honor ancestors, chiefs, or other important personages, However, no written and little oral history exists on the island, so it’s impossible to be certain.” (View Source)

So the real answer to the questions posed above is that no one knows for sure who built the amazing stone statues, or how they did so, or why. We also don’t know who carved the petroglyphs, or who created the sophisticated hieroglyphic script called Rongorongo.

Moai Restored by Western Archeologists

What we do know, however, is that the Polynesians themselves also do not know. We also know that similar stone Moai to those found on Easter Island have never been found on any of the other Pacific Islands that have been settled by the Polynesian people.

Furthermore, we know that all the fallen Moai that have been rebuilt on their traditional stone platforms, have been erected by western archeologists and not by the Polynesian inhabitants, who seem to express little interest in their care and preservation.

But, as we will discover in the following instalment, there is a possibility that all of the mysteries of Easter Island can be resolved if we examine the evidence detailed above from a different point of view – a point of view that validates the story told by James Churchward in his book The Lost Continent of Mu.