The Legend of Lemuria – Part One

In his written dialogue called Timaeus, Plato described how Solon, the famed lawmaker of ancient Greece who lived 600 years before the time of Christ, had travelled to Egypt where he was honoured for his wisdom and understanding.

According to Plato, while he was in Egypt, Solon had asked an elderly Egyptian priest if he could recount their earliest history. The priest replied:

“Oh Solon, Solon, you Greeks are all children, and there is no such thing as an old Greek…You have no belief rooted in old tradition and no knowledge hoary with age. And the reason is this. There have been and will be many different calamities to destroy mankind, the greatest of them by fire and water, lesser ones by countless other means.”

The idea that mankind has been destroyed many times in ages past as a result of natural catastrophes, is one that does not sit well with modern Historians, Geologists or Archeologists, all of whom pay homage to the dogma of Uniformitarianism.

Despite the fact that Plato is regarded today as one of the foremost Greek philosophers, having been a student of Socrates as well as the tutor of Aristotle, there is no room at the Inn of orthodox science for stories of past cataclysms, no matter how august their source.

Modern historians claim that the recorded history of mankind began with the invention of writing, which is believed to have begun in Mesopotamia around 3,000 BC, with Sumerian Cuneiform texts written on clay tablets. Egyptian writing, in the form of hieroglyphics written on papyrus, is believed to have begun about the same time.

It should come as no surprise therefore, that when a book was published in 1926 describing the existence of a towering civilization that dominated the world for hundreds of thousands of years, only to be destroyed in a world-wide cataclysm that has long since been forgotten, it was rejected as having no scientific credibility whatsoever.

The book was called The Lost Continent of Mu: Motherland of Man, and its author was a British born occult writer named James Churchward. In this book he claimed that, while he had been a soldier in India more than fifty years before, he had been befriended by a high-ranking temple priest.

The book was called The Lost Continent of Mu: Motherland of Man, and its author was a British born occult writer named James Churchward. In this book he claimed that, while he had been a soldier in India more than fifty years before, he had been befriended by a high-ranking temple priest.

As he later explained in a lecture he gave in Mount Vernon, New York, in 1931:

“This old Master and his two cousins, both older than himself, and he was over 70 years of age 50 years ago, were the sole survivors of the Naacal Brotherhood which had existed for 70,000 years.

“This Brotherhood had been formed in the Motherland, when experts of religion and the Cosmic Sciences were being sent from Mu to her various colonies. These three were the only ones left in India who understood the language of the Motherland, her symbols, alphabet and forms of writing.

“For seven years during all my available time, I diligently studied under this old Rishi, …with a view of finding out something about ancient man. At that time I had no idea of publishing my findings. I made the study purely to satisfy my curious self. I was the only one to whom this old Rishi ever gave instructions on this subject.” (View Source)

Churchward claimed that this temple priest had showed him two sets of ancient “sunburnt” clay tablets, supposedly written in the Naga-Maya language of Mu. He was told that these tablets had originated in the place “where man first appeared”.

Under the direction of this temple priest, Churchward learned how to read these tablets, and it was from this information that he was later able to describe the continent of Mu (also called Lemuria) as the home of an advanced civilization, which had begun some 200,000 years before.

Churchward claimed that Mu was the site of the original “Garden of Eden”, and that it was the home of the Naacals, a “white” race whose civilization was technologically more advanced than any other, and that Mu was the inspiration for later civilizations such as Egypt, Greece, Central America, India, Babylon, Persia and others.

He also claimed that the civilization of Mu was renowned for its megalithic architecture, involving cyclopean stones weighing up to hundreds of tons, that fitted together so perfectly that no mortar was needed to hold them in place. And although later cultures may have imitated their technology, they were but a pale shadow of the glory that was Mu.

Colonel Churchward’s map of Mu

According to Churchward, the continent of Mu was located in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, and that as a result of the greatest tragedy in the history of mankind, it was afflicted by a series of cataclysms and sank beneath the waves, carrying down with it some 63 million people.

He also claimed that, based on the writing on the clay tablets, the entire continent had been “completely obliterated in almost a single night”, and that after a series of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, “the broken land fell into that great abyss of fire”, and was covered by “fifty millions of square miles of water”.

Scientists today scoff at Churchward’s story of the civilization of Mu, and of the alleged lost continent of Lemuria, dismissing them both as mere fictional legends, especially since they contend that an entire continent could neither sink nor be destroyed in so short a period of time.

Besides, according to the latest geological knowledge of plate tectonics, continents are considered to be vast, solid blocks of lighter rock (continental crust), that float upon heavier rock (oceanic crust), much like icebergs float on water, and cannot simply sink suddenly beneath the ocean.

Furthermore, as we have seen in earlier posts, geologists base their views on the theory of Uniformitarianism, which posits that all earth changes take place over huge amounts of geological time, and that if an entire continent were to be displaced, this would require a time span of many hundreds of millions of years.

On the face of it, the evidence would seem to support the scientific point of view. If a continental landmass did once exist in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, it certainly isn’t there now. All that exists today are a series of atolls linked with a handful of tiny, volcanic islands that lie scattered many thousands of miles apart.

Based on an analysis of linguistic and cultural similarities of the region, it is generally accepted today that the first people to settle on these islands came from South East Asia. Successive migrations are believed to have taken place at different times following the last ice-age.

Starting around 1,600 BC, the population is believed to have spread to Micronesia (Marianne, Marshall archipelagos), and then to Melanesia (Papua-New Guinea, Solomon Islands), before moving on to Western Polynesia (Fiji, Tonga, Samoa).

The central archipelagos of the Cook islands, the Marquesas and the Society islands that make up Eastern Polynesia, are thought to have been inhabited at a later time, and these islands are considered to have been the source of subsequent migrations to the Hawaiian islands.

All of these island cultures were characterised by a simple yet ecologically sound lifestyle, with wooden houses built on stone platforms, and woven roofs made from coconut and pandanus leaves, using simple tools of wood and stone, before European explorers later introduced them to the use of metal implements.

But this is where Churchward’s tale becomes tantalizingly evocative, because although these different islands are separated by vast expanses of open ocean, they share enigmatic ruins that are at odds with everything that is known about the cultures that reside on these islands today.

The Water Planet

These ruins also pose the following question. Why, on a globe that contains so many different continents, is all the land that exists upon the surface of the planet limited to one hemisphere only? This can be seen from the image on the right generated by Google Earth. It is a simulated view of the earth from an altitude of 10,000 miles (16,000 kilometres), and is centred above 17ºS, 150ºW to the southwest of Tahiti.

Could it be, that in spite of the current theories of science, there really was at one time a continent located in the Pacific, and that the islands that now dot the ocean are all that remain of this sunken land, that was once home to an advanced civilization?

And if they really were once part of a greater whole, might there still exist on some of these islands fragmentary evidence of this ancient culture, particularly if it was renowned for its megalithic architecture, and its use of cyclopean blocks of stone?

Certainly, there are plenty of islands that have strange ruins involving the use of gigantic blocks of stone, some of which weighing many tons, that were never part of Polynesian culture. One of the most famous of these ruins can be found in the Caroline islands in the Western Pacific.

The Island of Nan Madol

Nan Madol lies off the eastern shore of the island of Pohnpei (formerly Ponape), that is part of the Federated States of Micronesia. It is a megalithic city consisting of a series of small artificial islands linked by a network of canals, built on top of a bed of coral, and is often referred to as the “Venice of the Pacific”.

The ruins of this ancient city cover an area of about seven square miles (18 square kms). These artificial islands were made by stacking large, hexagonal prisms made of black basalt. It is estimated that about 250 million pieces of prismatic basalt rock were needed to create the foundations of this megalithic city.

The largest structure at Nan Madol, called Nan Douwas, is oriented to the cardinal directions and consists of two concentric perimeter walls, separated by a seawater moat that encloses a pyramidal mound. The enormous cornerstone that lies on its southeastern side, weighs around fifty tons.

The ruins of Nan Madol raise a multitude of questions that have never been satisfactorily resolved. Why, for example, did the original builders go to the trouble of building artificial islands when they could have simply built on any of the natural coral reef islands nearby?

The ruins of Nan Madol raise a multitude of questions that have never been satisfactorily resolved. Why, for example, did the original builders go to the trouble of building artificial islands when they could have simply built on any of the natural coral reef islands nearby?

And why did they build a city of this size in a location that had no food or source of potable water? One has to go many miles inland to grow food and gather water. How did they feed the population? And what was the point of building the city in the first place?

The simple logistics of assembling such a vast quantity of basalt rock in one place are truly mind-boggling. The builders not only had to find a suitable quarry for the rock, but then had to meet the challenge of transporting this material, estimated to total about 700 metric tons, from its source to its final destination.

The current scientific theory is that the builders used wooden rafts to carry these basalt columns. But when the Discovery Channel tried to demonstrate the use of this method for a TV documentary in 1995, they were unable to find a way of transporting anything weighing over one ton.

Pohnpei’s only archeologist, Rufino Mauricio, who has dedicated his life to studying and preserving these ruins, confessed:

“We don’t know how they brought the columns here and we don’t know how they lifted them up to build the walls.”

He added that given the size of the population at that time, thought to be fewer than 30,000 people, the construction of Nan Madol was an even larger and more remarkable achievement than the Great Pyramid of Giza in ancient Egypt.

There is one further mystery about these island ruins. Many of these artificial islands are interlinked by a series of tunnels. And some of these tunnels have been found to continue underwater, in the direction of the open ocean.

The only explanation that seems at all logical to explain these mysteries is that one of two things must have happened. Either the level of the sea rose since these artificial islands were built, or the major part of the land has sunk, leaving the ruins partially submerged.

As amazing as the ruins of Nan Madol undoubtedly are, the relatively crude way in which these buildings were constructed, with basalt columns stacked one upon another, can hardly be mistaken for an ancient civilization renowned for its expertise in megalithic construction.

But they could have been built by a culture that had survived the original destruction of Mu, and still retained some of the knowledge that was used on Mu, such as the ability to create and move gigantic stones, even if they did not fully match the beauty and scope of the architecture of the Motherland .

However, there are other ruins that lie scattered around the Pacific Ocean that are truly cyclopean in size, that could easily be hundreds of thousands of years old. They speak of a long vanished past that could well validate the stories that were told to James Churchward by that old temple priest.

The island of Tongatapu in the Tonga Islands has a remarkable megalithic arch, that is the only one of its type to be found in the South Pacific. It is called the trilithon of Ha’amonga. Each of the upright coral pillars is about fifteen feet (4.9 metres) high, and weigh about fifty tons. The lintel, or crosspiece, which is set into grooves in the upright stones, weighs about nine tons.

The Mighty Trilithon of Ha’amonga

One of the cities on Tongatapu has an astonishing linguistic link with the continent of Mu. It is called Mu’a. Its ceremonial centre contains many megalithic platforms known as Langi. The largest of these, called Langi Tauhala, contains a single block of stone weighing over thirty tons.

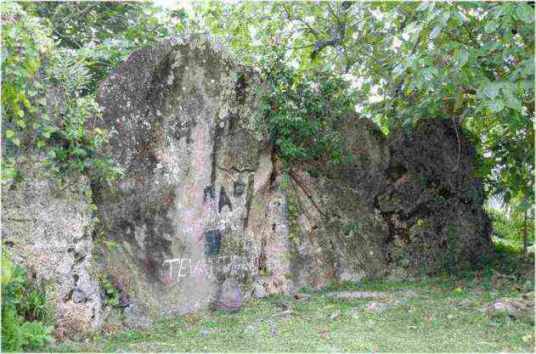

Part of the megalithic wall

The central area of Mu’a is surrounded by a canal, and has massive rocks that form part of a wall that extends over 660 yards (200 metres) on the lagoon side of the city. They suggest that at one time they might have been part of an ancient wharf where large vessels once docked.

Truncated, pyramidal platforms, known as Marae, have been found throughout the Society Islands. Some of them consist of megalithic stones that have been carefully shaped and fitted. The largest of these, known as Marae Mahaiatea, can be found on the island of Raiatea in the Leeward Islands. It has eleven steps and rises to a height of over forty feet (13 metres).

Similar Marae can be found on the islands of Tahiti, Bora Bora and Moorea. The remains of other great stone platforms built of cyclopean basalt blocks, some weighing over ten tons, can also be found throughout the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia. Covered with jungle vegetation, they stand today as mute evidence of a vanished civilization.

More ruins of great stone platforms and terraces, overgrown with jungle vegetation, can be found throughout French Polynesia. These platforms are made of cyclopean basalt blocks weighing up to 10 tons each.

One of the most impressive of these can be found on Nuku Hiva, the largest of the Marquesas Islands. The ancient ceremonial centre in the Taipivai Valley includes a massive platform, made again of basalt blocks. It contains an estimated 6,800 cubic metres of earth fill, and is 560 yards (170 metres) long.

The above sites are merely a few examples of the megalithic ruins that can be found on islands all over the Pacific Ocean. Additional information about further ruins can be found here.

The fact that these ruins exist at all is an enduring mystery, because they were never part of the Polynesian culture, and the Polynesians themselves have no idea who built these massive stone edifices, or how they managed such stupendous feats of engineering, that are so far beyond their own capabilities.

Yet even more mysterious stone ruins are located on one of the most remote islands in the southeastern Pacific Ocean. The Polynesians called this island Rapa Nui. We know it today as Easter Island, because the first European to visit it was the Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen, who encountered it on Easter Sunday in 1722.

Easter Island may be renowned for its unique stone statues known as Moai, but this tiny island also contains evidence of a far more advanced civilization than any that have been discovered elsewhere, as we shall discover in the following instalment.

July 12th, 2014 at 9:35 am

Im no pro, but I think you made a very good point. You certainly know what you’re talking about, and I can really get behind that. Thanks for being so upfront and so sincere.