Darwin’s Delusion – Part Two

The problem that Darwin’s theory of evolution squarely faces is that, in the century and a half that has elapsed since his ideas were first advanced, scientists have still been unable to unearth evidence of any transitional forms, despite every effort to do so.

Although vast amounts of evidence have been uncovered of variations within species, as well as examples of different species that closely resemble one another, scientists have not yet found indisputable evidence to link these different forms with one another.

In fact there has not been one single instance where fossilised evidence has been able to show precisely how one species has turned into another. Scientists have so far been unable to find evidence of aquatic life slowly turning into amphibious creatures, or amphibious life turning into reptiles, or of reptiles turning into mammals.

All that exists is simply evidence of different types of species. Those scientists who still support the Darwinian view have been satisfied to see in the existence of various related species, evidence of just those transitional forms which Darwin had expected to find.

Yet there is no case where the fossil record has left an unbroken track of minute changes leading from one distinct species to another. Darwin’s grand theory has still to be proved by a single example of one species being transformed into another by means of fine gradations.

Because the fossilised evidence is simply not there, a growing number of scientists have begun to ask whether it is not time to question the very principle on which Darwinian evolutionary theory is based, namely, the idea that one species does, in fact, change into another.

What the fossilised evidence does show, and show conclusively, is that different species have demonstrated a persistent capacity for remaining in the form in which they first appeared, over long periods of time. This span of time often extends over many hundreds of millions of years.

There are, in fact, many examples of species alive today which have not shown any propensity for change from the form preserved in the fossil records in the distant geological past. This seems a flagrant contravention of everything that Darwin postulated.

Since every species that exists today must, by definition, be a survivor or victor in the struggle for survival, and since by Darwin’s argument each species owes its survival to its ability to change its physical characteristics in response to changing conditions, those species which are alive today should not exist in the form that they did in ages past.

Furthermore, if nature’s habit was continually to transform life through varying stages of physical form in an ever-increasing process of sophistication, it is strange to find evidence of simple forms today which have for millennia been content to retain their rudimentary structure.

Resistance to Change

Put more simply, the challenge to the accepted theory of evolution is this. If simple forms of life have graduated slowly throughout history into more sophisticated forms, why is it that many simple forms of life have shown no inclination to change over periods of millions of years?

If these forms were truly transitional, they should by now have changed into other forms. Yet the evidence of the fossil record shows that this is not the case.

When a primeval fish like the coelacanth, which first appeared in the fossil record some 400 million years ago, and was long believed to be extinct, was unexpectedly caught in fishing nets off the coast of Madagascar in 1938, its appearance did little to warm the hearts of avid Darwinists.

Coelacanth

What had made the coelacanth so intriguing to biologists was the fact that four of its fins had developed into limb-like appendages. For this reason it had become known colloquially as “old four legs”.

Those biologists who were looking for evidence of marine creatures turning into amphibious life saw in the coelacanth a happy transitional form. But when an example of a twentieth century coelacanth was examined, it was found to have retained the exact form that was preserved in the earliest fossil record.

While Darwin confidently noted that “most of the other Siberian Molluscs and crustaceans have changed greatly,” 1 in the 1970’s, biologist Peter Williamson published evidence to the contrary. 2

After long evaluation of these primitive shell-like creatures, Williamson concluded that even though molluscs could be classified into lineages of related forms, each lineage was found to be static over long periods of time. They did not change, bit by morphological bit, into a new species. Instead, he found that they remained essentially unchanged until they finally became extinct.

Although it is clear that creatures within a particular species do change as a result of selective breeding, as can be seen with any species that has become domesticated, there is as yet no evidence that these changes lead, by fine gradations, into species which are completely different.

Because such changes within species have already been observed, biologists have extrapolated that changes between species have been the result of a similar genetic process.

Experiments in Mutation

Since the geological record has thus far been unable to verify Darwin’s theory by producing evidence of transitional forms, proponents of his thesis have attempted to prove it by resorting to genetic experiments.

By using species which reproduce extremely rapidly, scientists have artificially introduced genetic mutations to these species, in the hope of creating a species that is entirely new. Unfortunately, such experiments have so far failed to supply conclusive evidence that this is either possible, or the way in which nature actually works.

Experiments conducted on fruit flies, for example, have allowed scientists to monitor the effects of genetic mutations over a period of many hundreds of generations.

While they have been successful in breeding fruit flies with widely varying physical characteristics, such as large wings or small, and bristles which vary considerably in number and size, they have so far been unable to change them into another type of creature. Fruit flies have remained fruit flies.

While they have been successful in breeding fruit flies with widely varying physical characteristics, such as large wings or small, and bristles which vary considerably in number and size, they have so far been unable to change them into another type of creature. Fruit flies have remained fruit flies.

These genetic experiments have done little to confirm the Darwinian view of evolution. In fact, when nature has been allowed to take its course, it has been found that mutations which have been artificially bred into a species have tended to be bred out again.

The species has reverted back to its original physical characteristics. In short, nature seems to resent genetic interference, and when given the chance to do so, persists in reverting to the traditional form. This resistance to change as a result of genetic manipulation is officially termed “genetic homeostasis”.

Despite elaborate experiments designed to show that changes in the underlying genetic pattern can lead to changes in physical form, scientists have as yet been unable to persuade one species, under carefully controlled laboratory conditions, to change into another.

The twin columns upon which the entire structure of Darwinian evolution has been built have thus far been found to be unsupported by physical evidence.

Firstly, the paleontological record has failed to show evidence of those transitional forms necessary for one form to change into another. Secondly, attempts to induce these changes artificially by means of genetic mutations have failed to show evidence of any species that is distinctly new.

There are, however, still other problems associated with the traditional theory of evolution. As Darwin himself clearly recognised, his elegant theory was confounded by certain complex organs such as the eye and ear.

Organs of Extreme Perfection

Because these organs functioned by means of a variety of interdependent parts, Darwin referred to them as “organs of extreme perfection”.

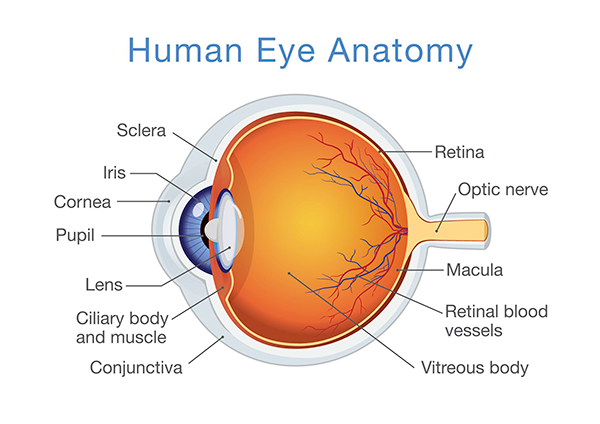

If we take the human eye as an example, if a person is to see effectively, a number of functions have to operate simultaneously and in harmony. The eye must be kept clear and moist, as a result of the activity of the eyelids and tear glands.

If we take the human eye as an example, if a person is to see effectively, a number of functions have to operate simultaneously and in harmony. The eye must be kept clear and moist, as a result of the activity of the eyelids and tear glands.

The light which enters the eye has to be focused by a lens precisely upon the retina at the back of the eye-ball. The amount of light which enters the eye must also be carefully controlled by the variable aperture of the iris. If any one of these interdependent functions is faulty, the person is unable to see.

Likewise, in the human ear, rhythmic variations in outer pressure must be matched by equivalent movements of a flexible eardrum. This eardrum is in turn attached to a set of tiny bones located in the middle ear, which all have to act in unison in order to transmit these vibrations to a fluid structure situated in the inner ear.

The Human Ear

For humans to hear at all, every part must relate perfectly to every other part. If there is a breakdown at any point in this process, nothing is ultimately heard.

The difficulty which confronted Darwin was all too obvious. If these organs of extreme perfection had themselves evolved through a variety of stages, then how was it possible for a species to survive while these changes were taking place? For as Lyall Watson has trenchantly remarked:

“The transparent cornea of our eye could hardly have evolved through progressive trial and error by natural selection. You can either see through it or you can’t. Such an innovation has to be right the first time, or else it just doesn’t happen again, because the blind owner gets eaten.” 3

Darwin’s essential thesis was that species survived as a result of their ability to evolve physically in beneficial ways. But if survival depended on the co-ordination of changes of such complexity that they could not be transmitted in the course of a single generation, then existence would effectively be terminated, thus bringing the evolutionary process to an abrupt end.

Faced with this dire dilemma, Darwin resorted to simple analogy.

“Yet reason tells me, that if numerous gradations from a perfect and complex eye to one very imperfect and simple, each grade being useful to its possessor, can be shown to exist; if further, the eye does vary ever so slightly, and the variations be inherited, which is certainly the case; and if any variation or modification in the organ be ever useful to an animal under changing conditions of life, then the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could be formed by natural selection, though insuperable by our imagination, can hardly be considered real.” 4

Darwin’s response to this difficulty was a splendid piece of intellectual legerdemain. He merely drew attention to a succession of eye types from the simple to the complex, and pointed out that variations in eyes could be inherited.

Then presto! By inferential deduction, it could safely be assumed that the simple eye had evolved into the complex by the process of natural selection, even though the method whereby it did so remained “insuperable by our imagination.”

Darwin did not deal at all with the question of survival in the interim. He merely glossed over this disturbing fact. For over one hundred years evolutionists have taken Darwin’s explanation at face value.

But in recent years, more and more biologists have refused to be convinced. There is no question, they agree, that eyes have evolved from the simple to the complex. But they claim there is not a shred of evidence to suppose that this has actually happened in the way that Darwin has described.

Neo-Darwinism

Darwin’s theory of evolution, or Neo-Darwinism which has since come to replace it, suffers from yet another massive disability. That is the impetus for evolutionary change.

Darwin advanced the idea that species were modified over many generations, “by the perpetration or the natural selection of many slight favourable variations.” 5 The key word here was “favourable”.

What made any variation favourable was obviously a modification which enabled a species to survive. The causes of these changes were attributed by Darwin to isolated, random events which occurred over the course of time.

The entire scheme of evolution according to Darwin, was ultimately due to chance.

Yet the idea that ever more sophisticated and complex forms of life could have evolved as a result of random changes of blind chance, has been a postulate which has increasingly strained the credulity of questioning scientists.

Nobel prize-winner Sir Ernst Chain voiced these concerns in 1970 when he wrote:

“To postulate that the development and survival of the fittest is entirely a consequence of chance mutations seems to me a hypothesis based on no evidence and irreconcilable with the facts. These classical evolutionary theories are a gross over-simplification of an immensely complex and intricate mass of facts, and it amazes me that they are swallowed so uncritically and readily, and for such a long time, by so many scientists without a murmur of protest.” 6

Darwin’s reliance on blind chance was not so much the product of his own thinking, however, as it was a consequence of the classical thought of the scientists of his day.

Since “purpose” was a concept which found no place in physical science, it would have been too great an imposition on the scientific paradigm of his times for Darwin to introduce it into his theory of evolution.

Yet his reference to chance flew in the face of all observation. Since there is hardly a human being alive who does not order his or her daily affairs according to a sense of purpose, and since this predilection has increasingly been observed in lower orders of life as well, the sterility of Darwin’s theory now lies revealed.

Yet despite the overwhelming tide of evidence ranged against it, there are still scientists today who profess that the universe is a purposeless affair.

The complete illogicality of their stance has been exposed by the British physicist Alfred Whitehead, who was moved to remark: “Scientists animated by the purpose of proving that they are purposeless constitute an interesting subject for study.” 7

The evidence that life has evolved through an increasingly sophisticated series of forms is beyond doubt. What is increasingly in doubt, however, is whether nature has acted in the way that Darwin has decreed.

The evidence of the fossil record has revealed two facts. One is that new forms of life have appeared very suddenly in geological time. These new forms of life have often displayed dramatic changes in structure, over periods of time that are much too short to explain by means of an infinite gradation of changes over innumerable generations.

Reptiles and Whales

The appearance of the whale, for example, occurred suddenly, without any contributing features in the reptilian realm. Being warm-blooded mammals, whales are assumed to have evolved from reptiles.

There is, however, one dramatic difference between the reptile and the whale. It is the motion of the tail. Whereas reptiles move their tails from side to side, the whale moves its tail up and down.

There is, however, one dramatic difference between the reptile and the whale. It is the motion of the tail. Whereas reptiles move their tails from side to side, the whale moves its tail up and down.

Tail of Whale

The successful evolution of this vital change in structure is so complex, involving so many skeletal changes of the spine and pelvis that it would have required far greater lengths of time to accomplish by natural selection than appears in the paleontological record.

Similarly, in order to fly, birds would have had to have undergone equally drastic changes, involving the entire reconstruction of their abdomens, from their reptilian ancestors.

Again, the geological record of fossils does not support the span of time that would have been needed for these changes, nor does it provide any evidence of those transitional forms necessary to accomplish such revolutionary changes in structure.

The second significant fact derived from the hisorical evaluation of fossils is that species have generally maintained a static form for long periods of time, before becoming extinct as unexpectedly and as abruptly as they first appeared.

Furthermore, the influence of genetic coding has seemed to serve, not as a method of transmitting tiny changes to offspring in ways which have led ultimately to a separate species, but as a means of preserving the unique form of the species concerned.

Genetic mutations have not enhanced a creature’s ability to survive. Instead, they seem to have contributed to its doom, thus allowing the species as a whole to survive in its original form.

Mutants, at all levels of nature, tend to die out. In short, mutations at the molecular level (micro-evolution) have not been shown to be capable of achieving inter-species transformation (macro-evolution) in the manner prescribed by Darwinian evolution.

Punctuated Equilibria

What the history of fossils has actually demonstrated is a process which is now referred to as “punctuated equilibria.”

In the course of history, different species have emerged unexpectedly in time manifesting distinctive features. These species have then maintained this equilibrium of form over long periods of time, before disappearing from the geological record as abruptly as they arrived.

In their place, distinct new forms have appeared which have then followed the same procedure. Evolution has thus come to be seen as a punctuated process. Nature has appeared to move in rapid and episodic leaps from one species to another. So the prime axiom of Darwin, ‘natura non facit saltum’ (nature does not make leaps), has not been borne out by the evidence.

Darwin’s elegant theory of evolution, which was heralded in the nineteenth century as a revelation of natural law, now rests on shreds of unfulfilled belief.

It has, in fact, so many fatal flaws that it has ceased to be a viable hypothesis. In short, its central thesis has been found to be unfounded. Darwin’s unique claim to scientific stature rested upon his notion that the process of evolution took place in a linear fashion, with one species blending inexorably into another, and with all forms of life being ultimately derived from a single progenitor.

If, however, one species does not change into another, as the evidence indisputably proves, then the entire framework of Darwinian evolution collapses. His classic work, The Origin of Species, becomes then little more than a historical curiosity.

And the grand dream of science, which was to explain the origin of the astonishing variety of species that have ever lived upon this planet, in terms of a single unifying theory along the lines suggested by Darwin, has proven to be a dismal delusion.

References

1 Charles Darwin, “On the Origin of Species“, Oxford University Press, London, 1902, p. 28.

2 Peter Williamson, “Morphological Stasis and Developmental Constraint: Real Problems for Neo-Darwinism“, in Nature, 294: 214-215, 1981.

3 Lyall Watson, “Lifetide“, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1979, p. 165.

4 Charles Darwin, op.cit. pp. 167-168.

5 Ibid, p. 432.

6 Ernst Chain, “Responsibility and the Scientist in Modern Western Society“, Council of Christians and Jews, London, 1970.

7 Quoted in “The Limitations of Science“, by John Sullivan, Mentor, New York, 1949, p. 126.

May 27th, 2014 at 12:40 am

Fantastic post however I was wanting to know if you could write a litte more on this subject? I’d be very thankful if you could elaborate a little bit more. Appreciate it!

July 2nd, 2014 at 11:45 pm

Howdy! Someone in my Facebook group shared this website with us so I came to look it over. I’m definitely loving the information. I’m book-marking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Terrific blog and wonderful style and design.